This was my fourth year working with Will Weltman and the Moniteau Marching Band. We’ve recently closed our season, the final football game being on October 25, 2019. We still have a parade for Veteran’s Day, and the band is headed to Florida right after Thanksgiving, but we are, essentially, done.

The kids talked Will into doing a Queen show this season, considering the movie Bohemian Rhapsody came out in 2018. I’d mentioned that to him in passing last season, but it always takes the kids to get him to come around.

Upon reflection (and, not going to lie, some help from some assignments in my class at SRU, SPED 325, Interventions in the Inclusive Classroom), I realized that I had already been using some great adaptations to what we were learning in order to get my kids to stay afloat, especially when we hit the ground running for the season.

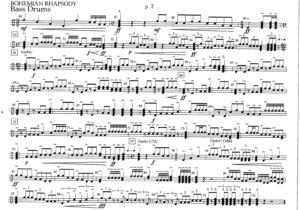

During band camp, way back in August, I was tasked with working with the bass drummers to finesse some of the more complex parts. If you’ve never seen a multiple bass drum part, it looks a little something like this:

That’s a lot of notes, right? Well, for the laypeople, this second page of Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen and arranged for marching band by Tom Wallace, is played by multiple bass drums. This particular part is written for four players, but our bass drum line only had three players.

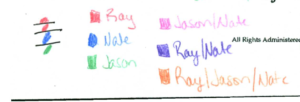

That meant we had a great deal of conversation about who played what. Eventually, we came up with a system.

Ray, who plays the smallest bass drum, would play the notes above the staff, and on the top space.

Nate, who plays the middle bass drum, would play the notes on the bottom space.

Jason, who plays the biggest bass drum, then would play the notes on the bottom space and below the staff.

So our staff ended up looking a little something like this:

Pay attention to those colors, cause they’ll come back. 😉

Pay attention to those colors, cause they’ll come back. 😉

If you’ll excuse my detour for a moment –

I SWEAR it’s relevant! –

I’m going to divulge something here:

I have ADHD.

That means my brain filters and processes information differently than most people. What’s hilarious to me, especially considering that I’m a musician, is that my auditory processing is not always 100% reliable. When learning music, I have to learn it in a very strict sort of way, to a specific process, before I can start applying any kind of interpretation, and learning by rote (by ear) is WAY harder for me than it probably should be.

That means, for me, and probably for people whose brains work like mine, I learn:

-

-

- Rhythms first! Rhythms are the building blocks of music! They determine how sound changes over time, and isn’t that just the most basic of definitions for music? (Hint: it totally is!)

- Pitches second! Rhythms are great, and make for some really interesting stuff – but do you have any idea how amazing it is to put the color into something with different pitches?

- Phrasing (including breathing plans and words/word sounds/vowels/etc – all those vocal things if you’re the singing type, like me and my barbershop chorus). This is where we take music from something primal and raw and turn it into emotions.

- Interpretation. How do we apply all those emotions and perform it so that others can understand?

-

So when I learn music, it’s sometimes helpful for me to make notes in my scores, especially accidentals and other twiddly things that my brain might skip over while looking at the big picture. I’ve also recently gotten into color coding my barbershop music while we’re still on paper, which gives me multitude reasons to use my fancy highlighters and pens to guide my eye into key changes, tempo changes, time signature changes, or for the more nuanced – key notes (how can I make “do” more special in a chord?), altered notes (those pesky accidentals – and their lousy alternate fingerings if I were playing an instrument!), and for me, my baritone notes that are higher than the leads (which is a complete mind-blower even after all this time – totally a different story, but we’ll get there, just not today!).

So anyway, back to the band!

The idea of color coding the music seemed fine enough, I supposed, but while I worked with these young men at band camp, it occurred to me that it wasn’t enough. For one, what happened when we all had to play at the same time, the same (or different!) rhythms? What about two of the three playing at once? How do we notate that?

Well, that meant we had to expand:

Now each combination has a color assigned to them, in addition to their original colors. (Note: the combination of Ray/Jason happened so infrequently that it was not worth it’s own color.)

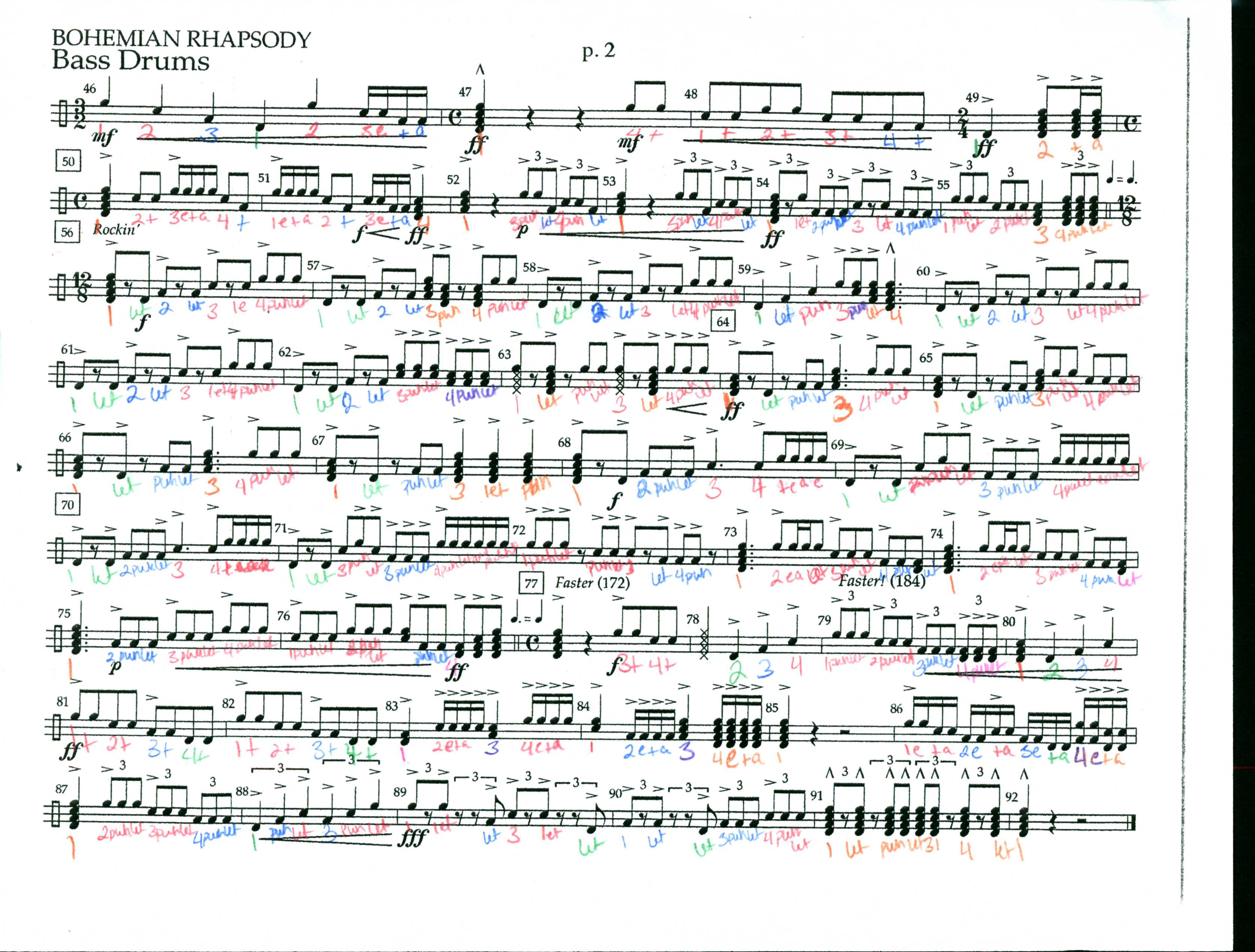

So one day, I brought them pencils and highlighters and we spent an entire afternoon sectional, writing out every single rhythm for each song. They did most of the work on their own, only pausing to check in once in a while for confirmation, but it did wonders.

In the end, that same second page of Bohemian Rhapsody ended up looking like this:

By forcing them to take the time to read each rhythm and think about how to count it, we drastically improved our playing of these songs – especially during inside rehearsals, where I was able to stay in close proximity and model some of the harder rhythms. Though, as time went on during the season, they needed me less and less, and I was relegated to the corner of the band room for after school rehearsals, keeping a sharp eye on my boys, watching them sheepishly grin in my direction when they forgot a part. “Don’t grin and shrug at me,” I told them when the drum major stopped them at one point, “Fix it. You know how.”

And they did.

Here’s a recording of that band playing at the Butler County Band Festival on September 25, 2019:

Adaptations aren’t just for special education. Every student can benefit from all of those things we talk about in our special education coursework. Chunking, color coding, graphic organizers, brain breaks, extra time, different modalities, manipulatives, etc.

It’s just up to us to apply it.

0 Comments